In this giving season, Atlanta’s leading philanthropists are helping fund efforts that are reshaping the city, the state and the world.

On Friday, international and U.S. philanthropic partners, including the Sandy Springs-based James M. Cox Foundation, announced the donation of millions of dollars to support efforts to protect the ecologically pristine Cochamó Valley in Chile, a wilderness in the Patagonia region of ancient forests, towering granite domes and turquoise waters.

The past two years have seen major gifts from Atlanta-area philanthropists as well as landmark foundation-backed project openings that will have profound effects in Atlanta and beyond.

Among them:

- Helping stop an effort to mine near the fragile Okefenokee Swamp.

- Funding for a landmark effort in Maine that could help lead to wild North Atlantic salmon being taken off the endangered species list.

- Contributing to major improvements at the city’s universities that could revitalize downtown Atlanta.

- Opening of a new state-of-the-art children’s hospital.

- Committing major funds to support youth mental health.

- Helping preserve wetlands within the Prairie Pothole Region of the Midwest and Canada.

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

The funding also comes in a moment when federal support of the arts, academic research, environmental protections and health care is in doubt.

These efforts are part of a long legacy of the city’s successful entrepreneurs using their wealth to help make Atlanta the modern global city it has become and protecting the environment for future generations, observers said. And they follow in the vein of gifts past that have led to the making or enhancement of such vital institutions as The Atlanta Beltline, Emory University, Grady Memorial Hospital, the Shepherd Center and The Woodruff Arts Center.

Over the decades, metro Atlanta has become home to major family foundations and international nongovernmental organizations, such as CARE, Habitat for Humanity, the Boys and Girls Club, American Cancer Society and the Task Force for Global Health. Major Atlanta corporations also commit tens of millions of dollars annually to supporting charitable causes.

In Atlanta, the 20th and 21st centuries have seen the rise of influential philanthropists and doers, including Robert Woodruff, Alonzo Herndon, John Bulow Campbell, H.J. Russell, the Rollins family, Roberto Goizeuta, John Imlay, the Selig family, Bernie Marcus, Arthur Blank, Diana Blank, Ted Turner, Harold and Alana Shepherd, Anne Cox Chambers and Jim Kennedy.

“We have a civic spirit that is in some ways the sort of traditional humble and behind-the-scenes kind of perspective on giving,” said Michelle Nunn, CEO of Atlanta-based humanitarian organization CARE and a co-founder of nonprofit volunteer network Hands On Atlanta.

“The culture of the of the civic leadership in the city is to do good work, but not to necessarily be always out front around bragging about it.”

But, she said, “I think they play an indispensable role.”

No single story could encapsulate all the work the myriad foundations — large and small — support in the region, nor could it include all the nongovernmental organizations and people funded by grants who are the boots on the ground.

But the common imprint of metro Atlanta’s philanthropists is a persistent and often behind-the-scenes effort to improve the lives of people in the region, the state, the nation and the world.

“All the great institutions here were created by people who just got together and said, ‘Let’s make this thing happen,’” said Alex Taylor, a trustee of the James M. Cox Foundation and CEO of Cox Enterprises, which among its holdings includes The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Early philanthropic pioneers

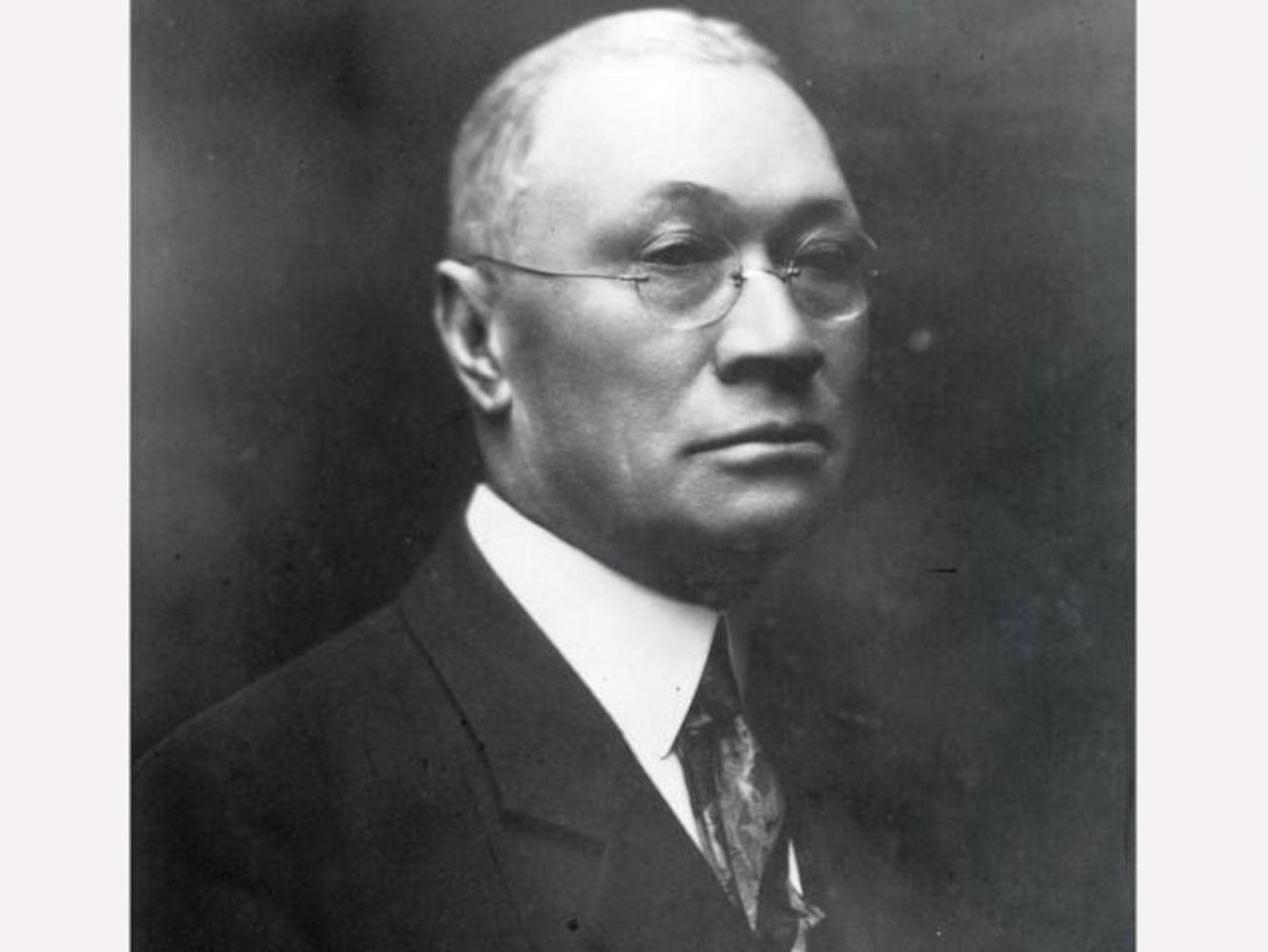

Alonzo Herndon, the son of a white slave owner and an enslaved woman, went from sharecropping in his childhood to Atlanta’s first Black millionaire from his string of barbershops, real estate holdings and the Atlanta Life Insurance Company.

Credit: Courtesy

Credit: Courtesy

But Herndon didn’t hoard the fruits of his success. He “gave generously to charities which he knew and to movements which he understood,” W.E.B. Du Bois wrote in 1927, a few months after Herndon’s death. He gave generously to the YMCA, Atlanta University, churches and orphanages.

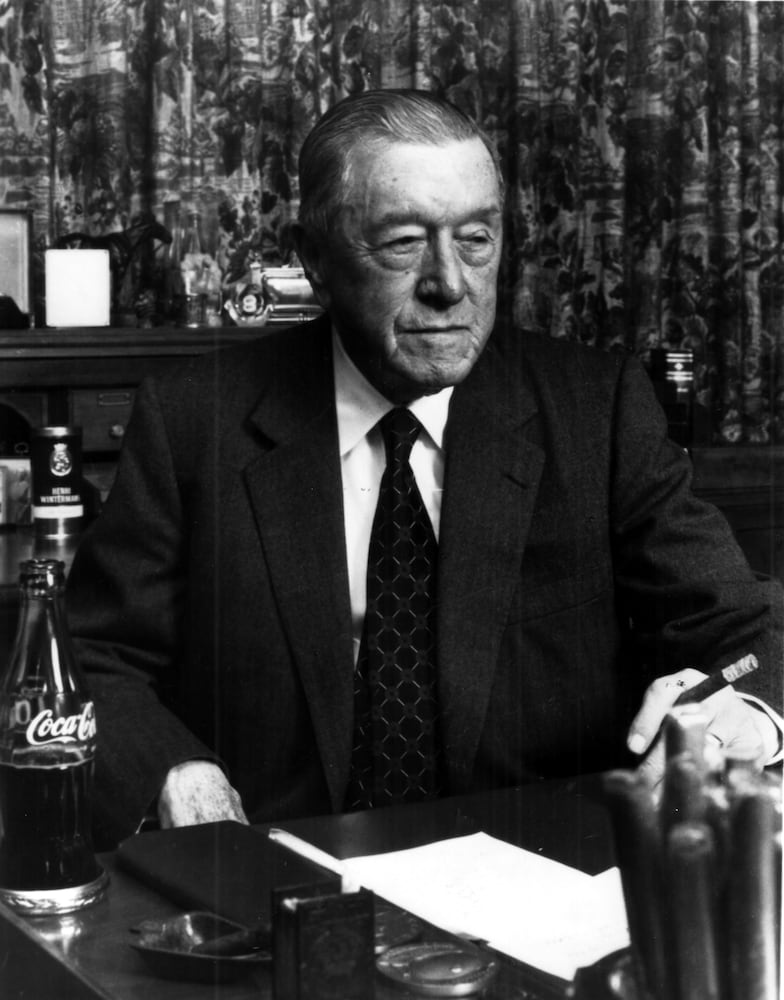

It may seem odd now, when many landmark Atlanta institutions bear the name “Woodruff,” but for most of Robert Winship Woodruff’s life he was the man known to Atlantans as “Mr. Anonymous.”

At the same time Woodruff was turning Coca-Cola into a global behemoth, he was quietly giving away hundreds of millions of dollars.

Pete McTier, former president of the Woodruff Foundation, said there is a civic spirit in the city that “has been alive in Atlanta for well over a century, whereby people come together and they decide what is important to try to accomplish, and they do it in large measure together.”

Herndon and Woodruff knew that for Atlanta to become the city it could be, it needed top-notch education, a clean environment, great health care, vibrant arts and to address social issues. The modern philanthropists of Atlanta have focused their giving on many of the same priorities and often with the intent of keeping the focus on the good works done by grant recipients.

‘Needed to give back’

Some of the biggest beneficiaries of philanthropy in Atlanta have been the city’s educational institutions. Going back to 1914, the founder of Coca-Cola Asa Candler offered $1 million and 75 acres of land to move Emory College from rural Oxford to Atlanta and establish Emory University.

Credit: SPECIAL TO AJC

Credit: SPECIAL TO AJC

Credit: Miguel Martinez-Jimenez

Credit: Miguel Martinez-Jimenez

Woodruff continued using the fortunes from Coca-Cola to enhance Emory. During his lifetime, Woodruff directed more than $320 million to Emory, including a landmark $105 million gift in 1979.

The Robert W. Woodruff Foundation has sister foundations that are also beneficiaries of Coca-Cola fortunes and provide grants for their own educational priorities as well: the Joseph B. Whitehead Foundation and the Lettie Pate Evans Foundation. His brother, George Woodruff, was also an active philanthropist, particularly supporting Georgia Tech.

In 2018, the Woodruff Foundation continued its long legacy of supporting Emory by pledging $400 million to the university for medical research and improved patient care models.

Another former chief executive of Coca-Cola, Roberto Goizueta, and his foundation helped reshape Emory’s business school, which now carries his name, and established an Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at the university.

Another Atlanta business magnate, O. Wayne Rollins, and his family foundation have contributed millions of dollars over the past 50 years to Emory. The family’s contributions have helped grow the Rollins School of Public Health into one of the top-ranked public health programs in the country.

Other higher education institutions have also been beneficiaries.

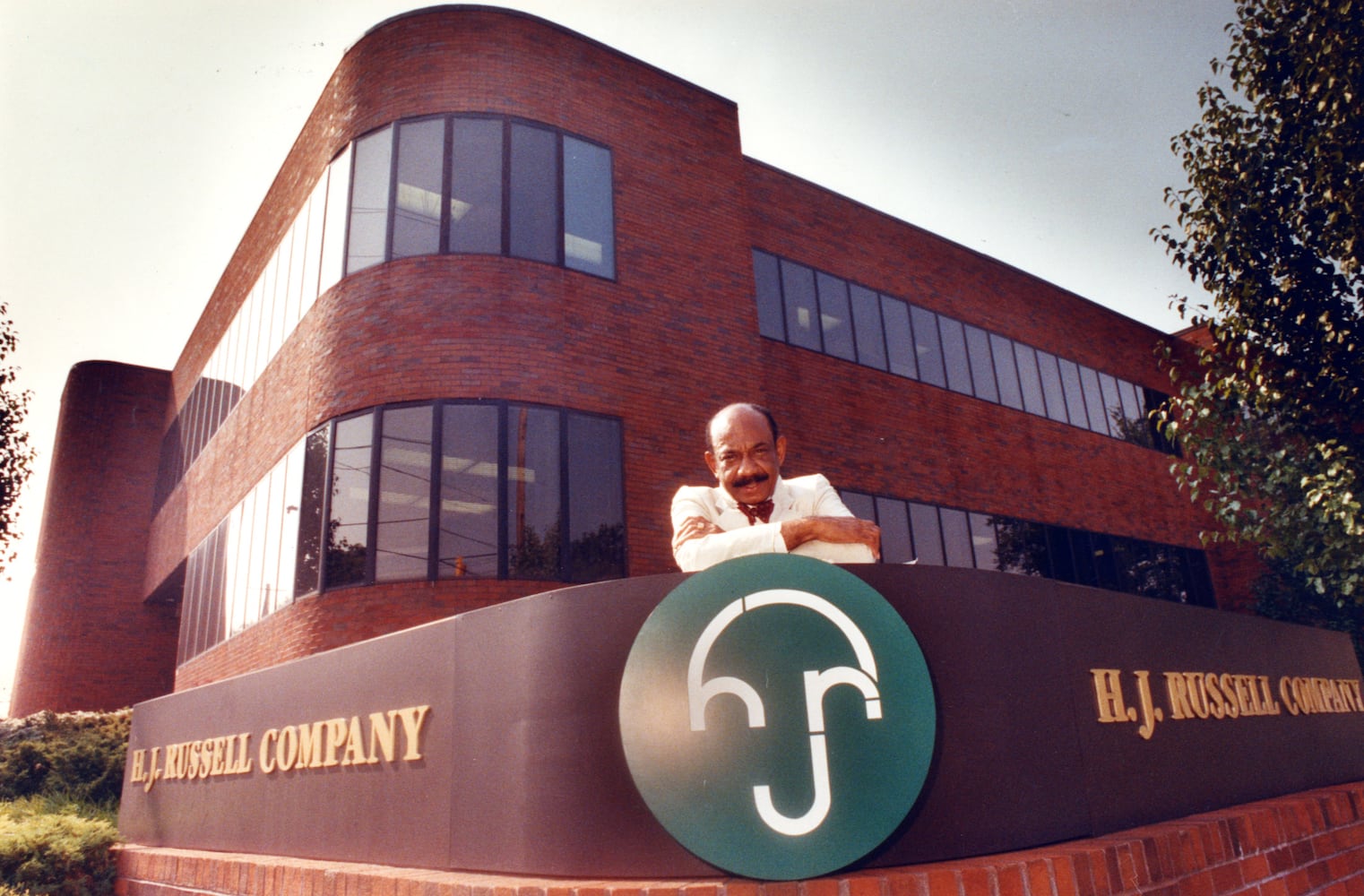

In 2006, the construction pioneer Herman J. Russell was one of the first Atlantans to contribute $1 million for the successful acquisition of King’s papers, now owned by Morehouse College and a part of the National Center for Civil and Human Rights.

He also gave $1 million each to Georgia State University, Tuskegee University (Russell’s alma mater), Morehouse College and Clark Atlanta University.

Russell, who died in 2014, recognized that “for all of the things that he had been given, the things he had worked for and the money that he made … he needed to give back to those that had less,” said Lovette Russell, his daughter-in-law and wife of his son Michael Russell.

This fall, the Arthur M. Blank Family Foundation announced a $50 million scholarship initiative for students at the city’s HBCUs.

Georgia State University’s downtown campus is being reimagined in part thanks to an $80 million gift from the Woodruff Foundation, the largest single grant in the school’s history.

Blank’s ex-wife, Diana Blank, has used her philanthropy to help Georgia Tech construct the Kendeda Building for Innovative Sustainable Design, now known as one of the most sustainable buildings in the world.

‘Untapped opportunity’

Many family and corporate foundations in Atlanta have made the environment and sustainability core to their giving.

Philanthropists did not dream up the Beltline, that idea originated with then-Georgia Tech graduate student Ryan Gravel. But it might not be here today if it wasn’t for pivotal early support from local foundations.

In 2005, the Blank Foundation gave the first publicly announced gift to buy parkland for the Beltline, which was then just a proposal hoping to gain steam in the community. The Woodruff and James M. Cox Foundations also provided pivotal initial support to the Beltline. In 2021, Woodruff pledged another $80 million to the project and in 2022, Cox committed $30 million to fund the completion of the Northwest Trails.

Atlanta’s philanthropists have also looked outside of the city and the vast natural beauty across the state and the country, working to preserve it for future generations.

In the 1970s, Woodruff was instrumental in helping preserve Ossabaw Island, a 26,000-acre barrier island about 20 miles south of Savannah. Then-President Jimmy Carter helped broker the deal between Sandy West, the island’s owner, and the state of Georgia. The state put up $4 million and Woodruff matched the other half.

Credit: AP

Credit: AP

The island is Georgia’s first Heritage Preserve, which restricts its use to scientific and cultural study, research and education, and preservation and conservation.

More recently, the James M. Cox Foundation and Cox Enterprises have provided more than $325 million to conservation and environmental stewardship causes, according to a news release.

“I don’t think there is a bigger, more pressing need than the environment, climate and the need for conservation in the world,” Taylor said. “I think it is the crisis of our generation.”

The James M. Cox Foundation’s focus on the environment goes back to the late 1950s. The foundation’s incorporating documents said it was to be used for the social good and the environment, according to Taylor.

Under James C. Kennedy, former chairman and CEO of Cox and current chairman of the James M. Cox Foundation, the organization has ramped up its giving. It was an original supporter of the PATH Foundation, starting in the 1990s, which has developed hundreds of miles of greenway trails across metro Atlanta, including the Beltline.

The foundation also founded the Food Well Alliance, replacing blighted intown properties with community gardens that provide access to fresh produce.

The foundation also is an active funder of small groups with big ideas that need seed funding. Both Food Well and PATH started small, and Kennedy likened philanthropy to venture capital, saying they both help scale ideas.

“If you can find those great ideas that just need some capital, that’s really exciting to us,” he said. “That is a great, sort of untapped opportunity to help people who actually are where the rubber meets the road and doing great jobs.”

The past year and a half has been an active time for the company and its philanthropic efforts. Last May, Cox Enterprises donated $100 million in Kennedy’s name to the wetland and waterfowl conservation nonprofit Ducks Unlimited for the Prairie Pothole Region, a network of wetlands in parts of the Midwest and Canada. The area’s trademark “potholes” — shallow lakes, seasonal ponds and marshes — were left behind as glaciers retreated from the area roughly 10,000 years ago.

Credit: Ducks Unlimited

Credit: Ducks Unlimited

The sprawling region sequesters carbon, and the wetlands are crucial not only for waterfowl but many plant and aquatic species, but it is threatened by agriculture.

“You really have to see it to understand it,” Kennedy said, calling the region “North America’s Amazon.”

The James M. Cox Foundation also recently gave funds to help a coalition of nonprofits purchase dams on the Kennebec River in Maine to allow for their removal, which could get Atlantic salmon swimming freely down the river again, Taylor said.

The project is potentially so impactful that it is expected to lead to the North Atlantic salmon’s removal from the endangered species list in the U.S., Cox officials have said.

This summer, the James M. Cox and Woodruff Foundations, among others, helped The Conservation Fund purchase roughly 8,000 acres from an Alabama company that planned to mine near the eastern edge of the Okefenokee Swamp, a project many scientists said threatened the vulnerable wetlands, which have been nominated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

On Friday, the James M. Cox Foundation announced it was donating $30 million to an effort to preserve the ecologically pristine Cochamó Valley in Chile, home to some of the oldest trees on Earth.

The land, akin to natural treasures such as Yosemite National Park in California, was at risk of being flooded to produce hydroelectric power and other potential development.

“It’s nice to know that if we die today, at least those things are safe,” Taylor said. “Everything else might be screwed up, but you make a difference in your little corner of the world, and maybe you inspire others to do the same.”

Healing

One of Woodruff’s first philanthropic projects was helping establish a cancer center at Emory after his mother was diagnosed with the disease. From those efforts the Winship Cancer Institute was born. Woodruff also helped bring the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to Atlanta.

In the decades since, the Woodruff Foundation helped facilitate the merger of Egleston Children’s Hospital and Scottish Rite Children’s Medical Center into Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta and led the effort to help save a financially precarious Grady Hospital in the 2000s.

But among all the health care projects in metro Atlanta, one of the most visible in the past five years is the Blank Foundation’s $200 million donation to CHOA for a new state-of-the-art hospital in Brookhaven, now named after Blank.

Credit: Miguel Martinez-Jimenez

Credit: Miguel Martinez-Jimenez

Fay Twersky, the foundation’s president and director, said Blank’s desire to give back comes from his mother, Molly, who instilled the Jewish value of “tikkun olam” in her sons, which roughly translates to healing and repairing the world.

“She just made it really clear that was an important value to her, and she hoped to impart that to them. And Arthur has just taken that very, very seriously,” Twersky said.

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Blank’s Home Depot co-founder, the late Bernie Marcus, used his foundation to contribute millions of dollars to causes, including the Shepherd Center, various centers at Grady and Piedmont hospitals, and the Marcus Autism Center.

Personal tragedy led to the creation of the Shepherd Center, one of the country’s leading neurorehabilitation hospitals. James “Harold” Shepherd Sr., the founder of Shepherd Construction Co., and his wife Alana started the institution in 1975 after their son had a traumatic spinal cord injury.

All told, Marcus, his wife and the Marcus Foundation have donated over $100 million to Shepherd. The Blank Foundation also recently gave $50 million to help fund housing for family members of patients.

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Credit: Miguel Martinez-Jimenez

Credit: Miguel Martinez-Jimenez

Marcus’ contributions to medical centers were “extremely important to who he was,” said Jay Kaiman, president of the Marcus Foundation, which has continued its philanthropic efforts beyond Marcus’ death last year.

“He understood the impact of what these clinical trials and what these programs could do to save lives.”

‘Great joy in giving back’

In 1962, a tragic moment for Atlanta led to arguably one the city’s most recognizable institutions. A plane carrying more than 100 Atlantans, mostly members of the arts community, crashed in Orly, France. Everyone onboard perished, leaving the city in mourning and wanting to help realize those citizens’ dreams of a culturally vibrant city, alive with theater, music and art.

Woodruff gifted $4 million, nearly half the cost of the complex’s construction, and the Atlanta Memorial Arts Center opened in 1968. It was later renamed Woodruff Arts Center in 1982. One of the founders of the James M. Cox Foundation, Anne Cox Chambers, was also a key player in establishing the High Museum of Art.

Credit: Miguel Martinez-Jimenez

Credit: Miguel Martinez-Jimenez

For Bernie Marcus, when he retired as CEO of Home Depot in 2001, he wanted to do something big for Atlanta, help rebuild downtown and make the city more of a destination. During Marcus’ travels for business, one of his favorite ways to relax was visiting an aquarium and walking around, according to Jay Kaiman.

The Georgia Aquarium, which opened in 2005, was built with a $200 million gift from the Marcus Foundation. It was Marcus’ first major philanthropic project.

Credit: AJC

Credit: AJC

It stands today near Centennial Olympic Park, a green space originally supported by philanthropists and business, including the Woodruff Foundation.

Credit: Seeger Gray / AJC

Credit: Seeger Gray / AJC

Kaiman said he thinks Atlanta’s corporate community has done a better job of giving back than, “for example, Silicon Valley, in terms of understanding how to give back and understand that there’s great joy in giving back and there’s great joy in being part of a community.”

It’s that community feel among executives that makes Atlanta unique, the city’s philanthropic leaders say.

Supportive ‘infrastructure’

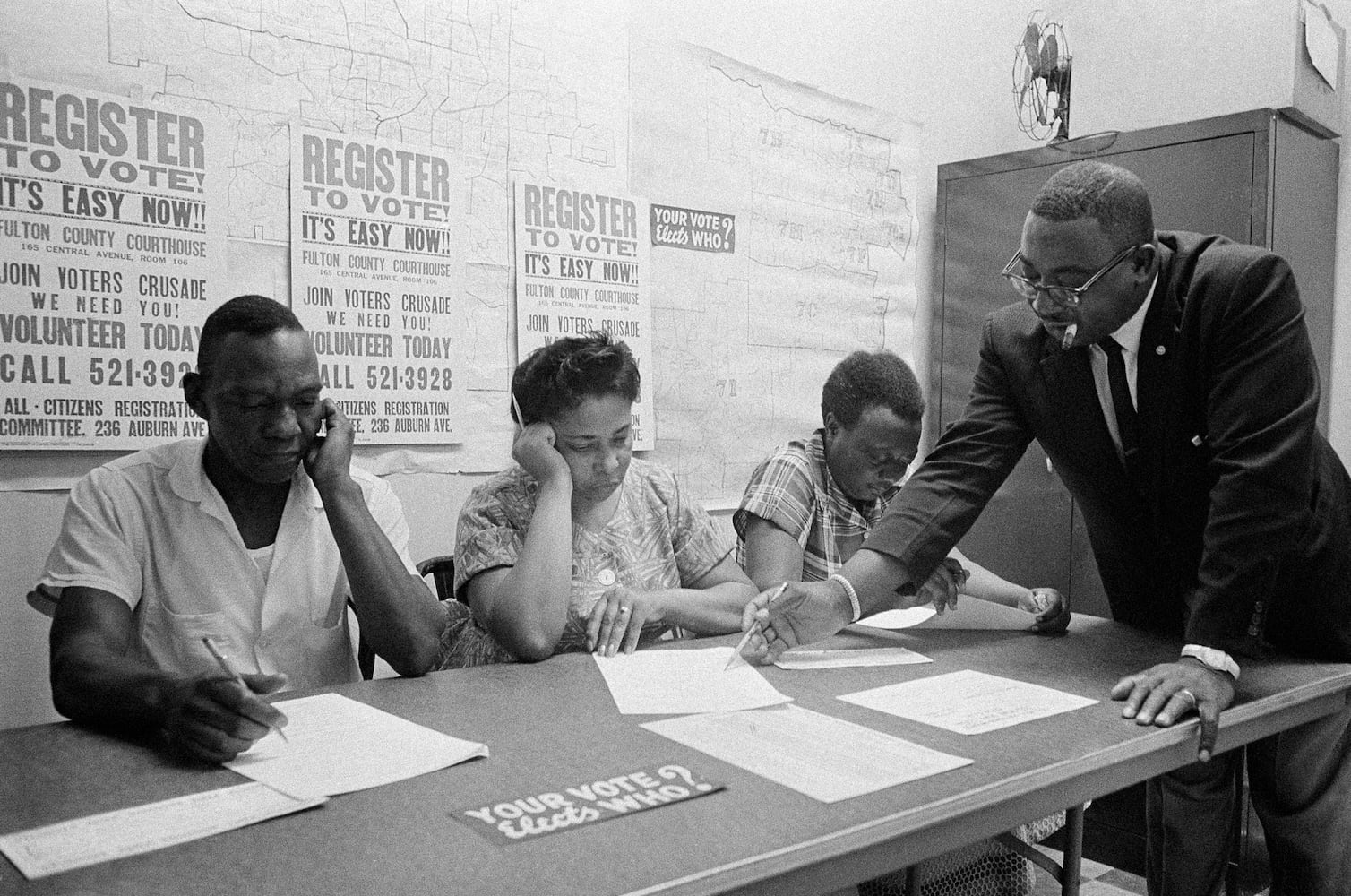

Norris Herndon in many ways followed in his father Alonzo’s footsteps. He created the Herndon Foundation in 1952 and was a strong supporter of the Civil Rights Movement.

In 1963 alone, the company donated at least $20,000 to King and various civil rights organizations. Atlanta Life also bought lunch for picketers around the country and bailed young protesters out of jail.

Credit: AJC

Credit: AJC

Woodruff helped the movement in small ways, too, getting Coca-Cola to sponsor the banquet to celebrate King’s Nobel Peace Prize, which in turn convinced Atlanta’s white business community to attend the dinner. After King’s death, Woodruff provided funding for the city to match a federal grant for the King Center, according to his biographer Charles Elliott.

At the height of the Civil Rights Movement, H.J. Russell made money available for bail bonds and was a heavy donor to King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

Lovette Russell said she saw that philanthropy was “a big part of the infrastructure that supported communities.”

“Without philanthropy, cities would not make it,” she said. “People would suffer. I mean, it’s really frightening.”

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured