DRY BRANCH — For almost three decades, Nancy Lubeck and her husband, Paul, have lived in a home tucked in the woods off a gravel road 30 minutes south of Macon.

For the Lubecks, there’s a lot to love about their slice of Middle Georgia. There’s the seclusion that life offers on 28 acres surrounded mostly by trees. There are surprise visits from wildlife, including members of Georgia’s most isolated population of black bears.

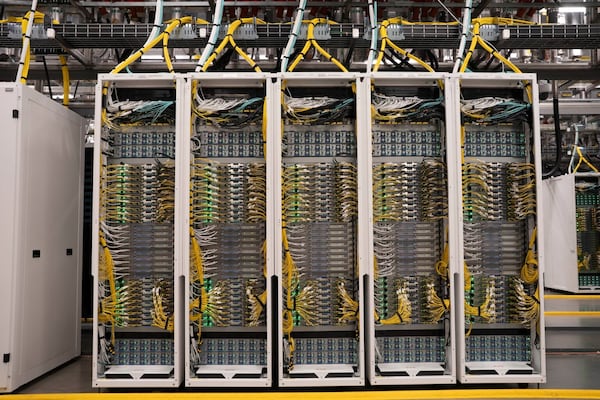

But earlier this year, the Lubecks learned they may soon have a new neighbor just a mile and a half down the road, one they fear will change the place they call home forever: a 300-acre data center complex. North Carolina-based developer Eagle Rock Partners wants to build warehouses filled with computer servers on timberlands near an ecologically and historically significant stretch of the Ocmulgee River.

That plan has stirred outrage across Twiggs County. Residents packed a series of question and answer sessions about the project held by the Twiggs County Board of Commissioners this fall. Despite the outcry, the board unanimously approved a request to rezone the land.

Signs urging locals to “SAY NO TO DATA CENTER” are scattered along Twiggs’ country roads, mirroring those planted in other rural counties across Georgia.

“The whole state pretty much feels like we’re under attack,” Nancy Lubeck said.

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

For much of the last three years, metro Atlanta has been one of the hottest markets in the country for new data centers. But as they’ve proliferated, Atlanta and many of its surrounding counties have banned or paused development of new server farms, a sign they’ve worn out their welcome in some communities.

The desire for new data centers to power artificial intelligence and other technology, meanwhile, has not waned. Now, prospectors are looking far outside the metro area for land and local leaders open to data centers.

“There’s advantages to being around population centers,” said Chris Gatch, chief revenue officer at Dunwoody-based DC Blox. “But there are a lot of reasons right now that make sense to put these things out in more remote locations.”

Far-flung corners of Georgia have larger plots of undeveloped land ripe for sprawling developments. Areas near existing power plants or large water sources can help lower the costs of building expensive new infrastructure that data centers need to keep servers online and from overheating.

While many towns across the country have embraced data centers as sources of tax revenue to fund schools and roads, some rural counties have temporarily banned data centers until their local codes can be reevaluated. Others are hashing out regulations in local meetings and town halls while they weigh multibillion-dollar projects.

“Government typically lags behind technology,” said Anna Roach, executive director and CEO of the Atlanta Regional Commission. “The rules, the laws, the zoning and all of that is catching up to this incredible resource in technology that has taken off at light speed.”

Some residents in Twiggs have filed a lawsuit challenging their elected officials’ rezoning decision. County commissioners and Eagle Rock — which is not named in the lawsuit — did not respond to requests for comment.

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Data center developers say the facilities will provide rural counties with jobs and an injection of tax revenue. Opponents, meanwhile, question whether the purported benefits are outweighed by the strain they place on infrastructure and resources. Some also fear the state isn’t doing enough to protect water, land and residential power customers from the influx.

“I’m not seeing any end to the state wanting to recruit these data centers, and that is a concern,” said Fletcher Sams, executive director of the Altamaha Riverkeeper.

‘It’s our turn’

Atlanta has become the darling of the data center industry since 2023, rapidly ascending to America’s second-largest market for computer storage facilities.

But the city’s Southern hospitality toward the sector has begun to sour. The industry’s power demands started to spark controversy, and concerns began to flare over hulking server farms close to transit corridors and residential streets.

The Atlanta City Council in September 2024 banned data centers near the Beltline, MARTA stations and bus-rapid transit stops. City leaders went even further in June to bar data centers from entire neighborhoods.

“As the market matures, these regulations start popping up,” said John McWilliams, head of data center insights at commercial real estate services firm Cushman & Wakefield. “They start trying to control where data center development happens.”

Credit: Miguel Martinez-Jimenez

Credit: Miguel Martinez-Jimenez

DeKalb and Clayton counties also issued their own moratoriums to prohibit new data centers from progressing to reevaluate their zoning codes. Edwina Clanton, president of the DeKalb NAACP, compared data centers to cigarettes, urging local leaders to ensure there are no unforeseen chronic consequences before approving new projects.

“Cigarettes were once considered harmless until families began paying the price with their health and their finances,” she said. “Now, we know that we did not have enough information about cigarette use to make a better-informed decision. … Data centers have the same potential for DeKalb County.”

The data center industry and its lobbyists repeatedly say they want to be good neighbors, touting the massive amounts of investment and tax revenue they’re bringing to the table. They also deny claims that proximity to data centers could have adverse health impacts like some other large industrial projects.

Historically, data centers needed to be near urban areas to have access to fiber-optic cables, which make up the internet’s nervous system. But those cables, which transmit data at the speed of light, have become a robust network stretching across much of the country.

Fiber access isn’t the constraint it used to be, said Andrew Alves, senior vice president of acquisitions for data center developer Digital Realty.

Some data, like information that powers autonomous vehicles, can’t afford even a few milliseconds of lag. Facilities called carrier hotels have to be located in urban areas as connection points between other data centers. But other technology can work as intended even with servers that are hundreds of miles away.

“They don’t always have to be near enterprises and eyeballs,” Alves said.

Credit: Courtesy of Microsoft

Credit: Courtesy of Microsoft

That leaves access to electricity, water and land as the main boxes to tick for a viable data center, and developers have found many rural sites they say pass with flying colors.

One of those is about 12 miles from Lake Lanier in Hall County. Developers Chris Hoag and Cameron Grogan are pursuing a data center under the code name “Project Turbo” with a capacity of up to 500 megawatts at a 145-acre parcel off O’Kelly Road. Hoag said it’s abutted by a chicken rendering facility and a liquid asphalt plant, not homes, and has ample access to power infrastructure.

First proposed in August, the project has been steeped in local controversy. Rich Elsarelli, chairman of the Hall County Republican Party, said the project’s scale and resource demands caught many residents off guard.

“These things come in waves, and it seems like it’s our turn,” he said. “I think you’re going to see more and more of these popping up in rural areas because that’s where your resources are.”

Credit: Courtesy of Project Turbo LLC

Credit: Courtesy of Project Turbo LLC

Daniel Graham, a resident of the county seat of Gainesville, said he doesn’t associate Hall County with tech-oriented industries. He attributed the developers’ interest to cheap land and loose regulations, adding that he’s concerned about what its water usage could mean for Lake Lanier — a vital regional resource that was the center of Georgia’s “Water Wars” litigation with neighboring states.

“I don’t want people in my city and in my county competing with some kind of corporate data center for water,” Graham said. “I value people being able to bathe and cook and clean and drink much more than I value cooling servers for data that’s making money for (large tech companies).”

Grogan pushed back on the fears that Lake Lanier’s water level is threatened by his proposal. At a forecast use of up to 225,000 gallons per day, the project would use significantly less water than many other proposals across Georgia.

“There’s fear and (people saying), ‘Save our lake, save our lake!’” Grogan said. “We’re not going to impact that lake.”

A dearth of information

As Georgia grows as a data center hub, some fear the state still has a blind spot when it comes to the resources the facilities consume — especially water.

The servers humming away inside these warehouses give off heat. To keep their pricy computer chips from frying, most facilities use water — sometimes significant amounts.

The $10 billion Butts County data center and hospital complex backed by Lt. Gov. Burt Jones’ family plans to use an estimated 4.5 million gallons of water a day, according to filings submitted to a state planning agency. That’s more than the 4 million gallons the county’s largest water plant can treat on a daily basis.

One of the few ways to track data center resource demands is the Development of Regional Impact process, an infrastructure study the Georgia Department of Community Affairs typically requires for large projects. DRI reviews are often the public’s first glimpse at the power, water and infrastructure needs of major developments.

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Late last month, the department approved new regional planning procedures for data centers above a certain square footage. But before that, the DRI process had been paused for months while the agency crafted the new data center guidelines.

The hiatus triggered worries that communities were effectively blindfolded while data centers surged. Even with new disclosure rules in place, Sams of the Altamaha Riverkeeper says there’s still a troubling lack of information available.

Of the 26 data centers he’s tracking across his vast river basin that stretches from Middle Georgia to the coast, he said he has water withdrawal estimates for fewer than half.

“There’s not enough information for me to tell you what the water impacts are,” Sams said.

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Data centers’ electricity needs could also affect water availability in the Middle Ocmulgee River Basin, where the Twiggs County server farm and others have been proposed.

The Middle Ocmulgee’s most recent regional water plan estimated the area’s annual average daily water demand would increase less than 1% by 2060. But that plan was finalized in 2023, just as data centers were starting to flock to Georgia.

The main assumption behind the small uptick expected? The closure of Plant Scherer, the massive Georgia Power-owned coal power plant outside Macon, which had been slated to close in 2028.

Credit: Elijah Nouvelage

Credit: Elijah Nouvelage

Now, that’s not happening anytime soon. This summer, Georgia regulators voted to keep Scherer running indefinitely to help provide around-the-clock power for data centers.

The state will start developing new regional water plans next year but won’t finalize them until 2028.

The Georgia Environmental Protection Division, which leads the state’s regional water planning, said data center consumption will factor into the new plans, but said it believes there’s “sufficient information to assess future water needs and make appropriate water withdrawal decisions.”

In the meantime, some who live in rural counties now considered prime real estate for data centers fear this is just the start. Some, like Julia Asherman, the owner of Rag & Frass Farm in Twiggs County, are skeptical that the money Big Tech is splashing on farmland will be a boon to local communities.

“It feels like there’s a ripple effect happening,” Asherman said. “And I don’t think it’s clear that the beneficiaries of that are going to be us, the regular people.”

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured